Emotional eating and impulse control is an aspect of feeding ourselves that is almost solely psychological. It’s a broadly interpreted term that means many different things. Boredom eating qualifies as emotional eating, as does stress eating and eating when you’re sad or scared.

“Emotional eating is basically just eating for any reason other than physical hunger,” says Nicolette Fraza, a Registered Dietitian based in Rhode Island, who says emotional eating and boredom eating are two of the top concerns she sees in her practice.

“But it doesn’t have to always be a negative thing,” she points out, acknowledging that positive emotions like excitement or desire can also be triggers. “There are social and cultural aspects to it. I once heard an interview with a psychologist,” she continues, “who pointed out something interesting. When you are in utero, it’s this safe, warm place where you don’t have to worry about anything; you’re being constantly fed. And then, when you’re born, it’s cold, you don’t know where you are, and the first thing you do to find comfort is to eat.”

“It’s just an innate thing for us to reach for food to find comfort. I actually don’t think it’s a bad thing to reach for food for comfort, but if you are numbing your feelings with food, without addressing the underlying emotion, that’s a problem.”

“Trying to address the emotion by doing something else for a little bit is a good idea, and then if you still have that intense craving, go back and enjoy it mindfully, and hopefully by addressing the emotion first you can actually enjoy the food a little bit more,” Fraza explains, touching on the impulse that brings people to food in the first place.

Mindful eating when you really do want something indulgent, for example, in turn, makes people more satisfied so they won’t have any or as many lingering cravings or guilt afterward.

Still, cultural triggers persist. Cake at the office party is another example of a time you eat when you might not necessarily have wanted it, but you go along with the flow. Many people also have grandmothers who “push” food– another ubiquitous cultural example that is magnified in different ethnic groups.

So what are some helpful hacks that people struggling with emotional eating can practice to improve their habits?

We mined the research from Tufts University Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Columbia’s Institute of Human Nutrition, Stanford’s Adult Eating and Weight Disorders Program, and NYU’s Department of Nutrition and Food Studies. We also spoke at length with Fraza, who has her finger on the pulse of what clients learn when they finally visit a nutritionist to address emotional eating.

Mindfulness at Mealtimes

“I approach this issue from the angle of mindfulness,” says Fraza, who asks clients to check in with the Hunger-Fullness Scale, also known as the Hunger-Satiety Scale, before each meal.

“The Hunger-Fullness Scale is a scale of 1 to 10 in which each number corresponds to a designated feeling that you can identify. For example, 1 would mean that you are completely famished, starving, feeling weak, maybe even nauseous. Meanwhile, 10 would be like you’re so uncomfortably full you could also maybe feel nauseous. We associate this feeling with ‘after Thanksgiving,'” she quips.

“Ideally, we try to get people to stay between a 4 and a 7, and to stop eating when you’re 80% full. At this point, you should feel satisfied but not overly full.” This, according to Fraza as well as data from Berkeley and Tufts, is easier said than done.

“A lot of people are not familiar with their hunger and fullness cues,” Fraza explains. “We eat for so many reasons other than hunger. For example, because it’s a certain time of day. We also eat socially– like if your coworkers are eating lunch so you eat with them.”

“But we’re told for so long [the grand scheme of our life] when to eat… like when we start school, we’re told we need to designate specific times to eat. As a result, I think a lot of people are out of sync with their actual hunger cues. Even just starting to be able to identify those cues without judgment and figuring out, ‘Am I hungry?’ It’s a practice that requires getting used to what is going on in your body.”

That, says Fraza is where using the hunger scale comes into play. In her nutrition and gut health courses, she has clients do a practice of rating their hunger before the meal, in the middle of the meal, and at the end of the meal. “But it also just helps with slowing down and bringing a more mindful aspect to eating,” she adds. “It’s actually ideal to chew your food 30 times before swallowing, but most people do like 15 chews.”

Noticing the texture and smell of the food throughout the meal is also important. When you do this, studies show that people eat far less but still feel satisfied. The University of Rhode Island, where Fraza trained, has conducted many studies that prove the effectiveness of using this kind of mindfulness to improve emotional eating outcomes. When practiced regularly, people end up enjoying food more, eating less, and actually feeling satisfied.

The goal is to get in touch with your biology and what feels good for you. Food should not be an escape from your workflow or an exhale from everything else. It’s not something to check off the To-Do list or to do while you’re distracted. Eating is its own activity.

So what is the practical application of the Hunger Scale when it comes to truly emotional eating? In severe cases of emotional eating, people should actively use this check-in scale before meals. Over time, incorporating it regularly, you start to just intuitively use it.

So effective is this strategy that HIPPA Compliant telehealth platforms now allow for food journaling that some nutritionists like Fraza use with clients. In several cases, having an automated system can encourage compliance because it’s already there for people to use before and after a meal.

Make A Check List of “Emotions & Actions”

“It can be helpful when you realize you’re going to eat to take a few deep breathes and pause, and check-in with your hunger scale. IF you are physically hungry, you should eat, says Fraza. “But if you aren’t, then you should ask yourself, ‘What emotion do I need to address right now?’ ”

Fraza has her clients make a list of some things they should do instead for each emotion. For example, “If they’re bored, what are a few things they can do? If they’re lonely, what can they do?”

“I think at that moment, it can be hard because you’re already in [the place of experiencing a craving]. But if you already have a list of things you can do, you can call a friend and go for a little walk, instead. Or, take a bath, journal, listen to music, or paint your nails. It kind of takes you away from that moment for a little while.” (Or at least long enough to realize if you are actually hungry.)

“Thinking about triggers is a way of getting out of the ‘autopilot’ state of mind that leads to emotional eating,” confirms Debra Safer, MD, an Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University Medical Center, as told to Tufts Health & Nutrition Letter. (Safer does research for Stanford’s Adult Eating and Weight Disorders Program.)

Once the so-called autopilot is turned off, Safer says, you can start developing healthier responses, like those that Fraza suggests above. (This is particularly interesting because this aspect of emotional eating is unlike other aspects of mental wellness. In broader mental health parlance, distractions can become what therapists sometimes refer to as “avoidance behavior”. When it comes to social-emotional hunger cues, however, distractions can be good.)

Know Your Triggers & Follow A Routine

If you’re a boredom eater rather than an emotional eater, then making sure that other aspects of your life are in order can also help. Here are some facts you should know:

- First, sleep deprivation can trigger certain cravings. In addition to working on getting better sleep (through better sleep hygiene, herbal remedies, or other palliative measures) eating balanced meals can help take the edge off. Make sure your meals consist of non-starchy vegetables, healthy fat, protein, and complex carbs. Avoid refined sugar and artificial caffeine drinks, as these only aid and abet cravings that stem from sleep deprivation.

- If you are eating out of boredom or because you are sleep-deprived, consider taking a nap. Sleep with the expectation that you can eat when you wake up.

- Also, make sure you eat fairly regularly. When you don’t, you’re more likely to just reach for whatever is in front of you.

- Stay hydrated. Many times, with boredom eating, people are not drinking enough water, especially if they are at home. Hunger and thirst can often present in the same way, as most people know.

- Warm liquids, says Fraza, can also be soothing and combat boredom eating. “Sipping broth or tea in between meals can help with boredom eating,” she confirms.

- Researchers at Tufts suggest chewing gum when you’re triggered to eat. “Keep some flavored chewing gums at hand,” they write, “Preferably sugarless versions. These can help because they involve chewing, an essential part of the eating experience.”

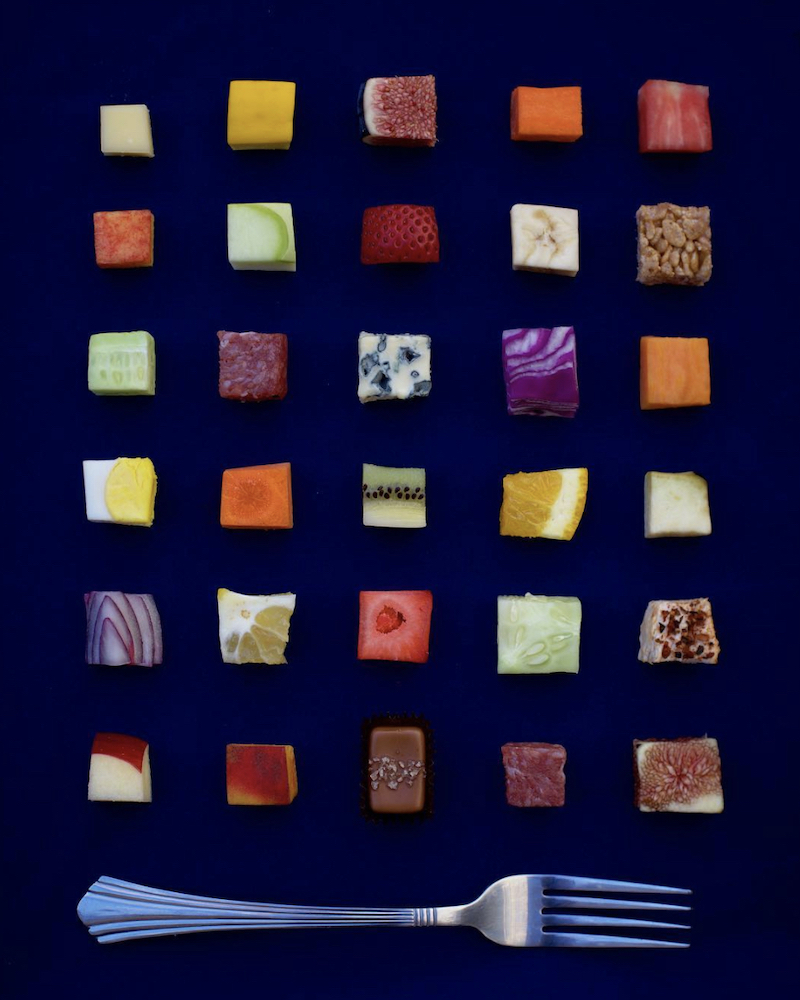

- Keep a bowl of fresh fruit on the kitchen table or counter. Research shows that emotional eating often has less to do with self-control and more to do with exposure and convenience. We tend to eat the things we see more of in our homes and work environments. Make sure that fresh, healthy foods are washed and ready to eat in your fridge. (Think baby carrots, apples, and oranges.) Similarly, plan to store cookies, chips, and other junk food behind closed cabinet doors. (Or better yet, don’t keep any in the house at all.) The idea here is to create situations that optimally support your goals.

- Having a morning routine can also help. “It’s a way to set yourself up for a successful day, says Fraza. “Even if you only have ten minutes, you can still have a morning routine. I have two kids, so my mornings are chaotic, but I still try to get a routine in. I like to write down something that I’m grateful for. Then, I do some light stretches, and I like to make coffee, which I find very meditative. Even if it’s just as simple as getting in a short walk or doing meditation. Anything that you can do every morning, regularly to get into that routine is helpful. There’s something in your brain waves. If you set yourself up in the morning, you’ll be more conscious of your behaviors throughout the day.”

“Also remember that unless you have diagnosed binge eating– so you’re either bored eating or emotional eating– it really is more of a habit, which can be addressed by just taking the time to replace it with a better habit,” says Fraza.

“It can feel resistant in the beginning because you have to form new neural pathways and keep doing it. But it will get you [away from emotional eating] eventually, so it’s just important to remember that and not to have any shame about it.”

Ultimately, you have agency when it’s a habit rather than a disorder.

Learning From Children’s Habits

What can adults do to set children up to have the right cues around food?

First, and perhaps most obviously: don’t use food as a reward. “Kids naturally have really great hunger cues and they are in tune with them; I think that we just mess it up,” Fraza explains.

“There was a high-profile study in which researchers gave kids endless amounts of whatever food they wanted. And it was always available,” says Fraza. “[Kids] were able to pick and choose what they wanted to eat for that week, and it was always available for that week. By the end of the study, they were able to balance out their meals so that they met all of their nutritional needs… even if they did eat only ice cream for one of those days. Ultimately, they were never hungry or too full.”

Children, moreover, inherently know how to self-regulate. It’s usually the adults who let emotions, stress, or scheduling get in the way of feeding themselves properly.

Fraza’s advice squares with what prominent pediatric dietician Ellyn Satter writes about in her book, Child of Mine: Feeding with Love and Good Sense. According to Satter’s methodology, Parents should choose the what, the where, and the when of eating. But in the ideal scenario, the child gets to choose if and how much.

In theory, if a child only wants to eat part of the meal, then that’s fine. If they decide at dinner that they are not hungry, that’s fine, too. Just make healthy snacks available later before bed. This way, kids know that if they are not hungry at that moment, there is an opportunity to eat later.

Still, Fraza notes, offering structured meals around the same time each day is good, too. “It’s better to teach them to come back and ask for food when they’re actually hungry rather than forcing them to eat a meal,” she explains.

If you look at the research currently espousing the health benefits of intermediate fasting and how it’s so good for longevity, weight management, and disease prevention, kids naturally follow this pattern, too. Sometimes, they just don’t want to eat dinner. Other times, they do.

There’s a connection here in our biology, moreover, that begs further exploration. Still, it ultimately lends more credence to the age-old expression that there’s value in “going with your gut”. Being mindfully in touch with your hunger cues, like children often are, can make all the difference.

Being Too Hard On Yourself Makes Stress Eating Worse

Finally, when it comes to emotional eating, it’s important to remember not to be judgmental about the problem. Many nutritionists and psychiatrists invoke this principle from Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, or DBT.

This is because the human brain learns emotional eating patterns by association. This leads to suboptimal associations between emotional triggers and food. Therefore, accepting emotional eating habits is ultimately a big part of the solution. Don’t waste mental energy stressing about it. (This is easier said than done, but important to remember.)

Letting go of shame is particularly impactful because self-criticism over emotional eating can become a trigger for more emotional eating. It’s a destructive cycle. When you forgive yourself, you free up the mental energy to learn new, better habits to replace old dysfunctional ones.

Having grace for yourself is key. It’s a mental capacity we all have that is constantly evolving. As such, it liberates us to grow, transform, and become the best versions of ourselves. Thus, when you arrive at a place of acceptance, you can quite literally have your cake and eat it, too.

***

Related: Try this 5-Step Method for Identifying Misplaced Emotions.

Leave a Reply