Sometime in the year 2000, Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke sat for an interview on Dutch television about the making of Radiohead’s Kid A and the rough time he had separating his personal life from the world of celebrity after the monumental success of 1997’s Ok Computer.

In this interview, Yorke relayed an anecdote that has stuck with me ever since and endeared me to Abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko, an artist whose work I now love directly as a result of this story.

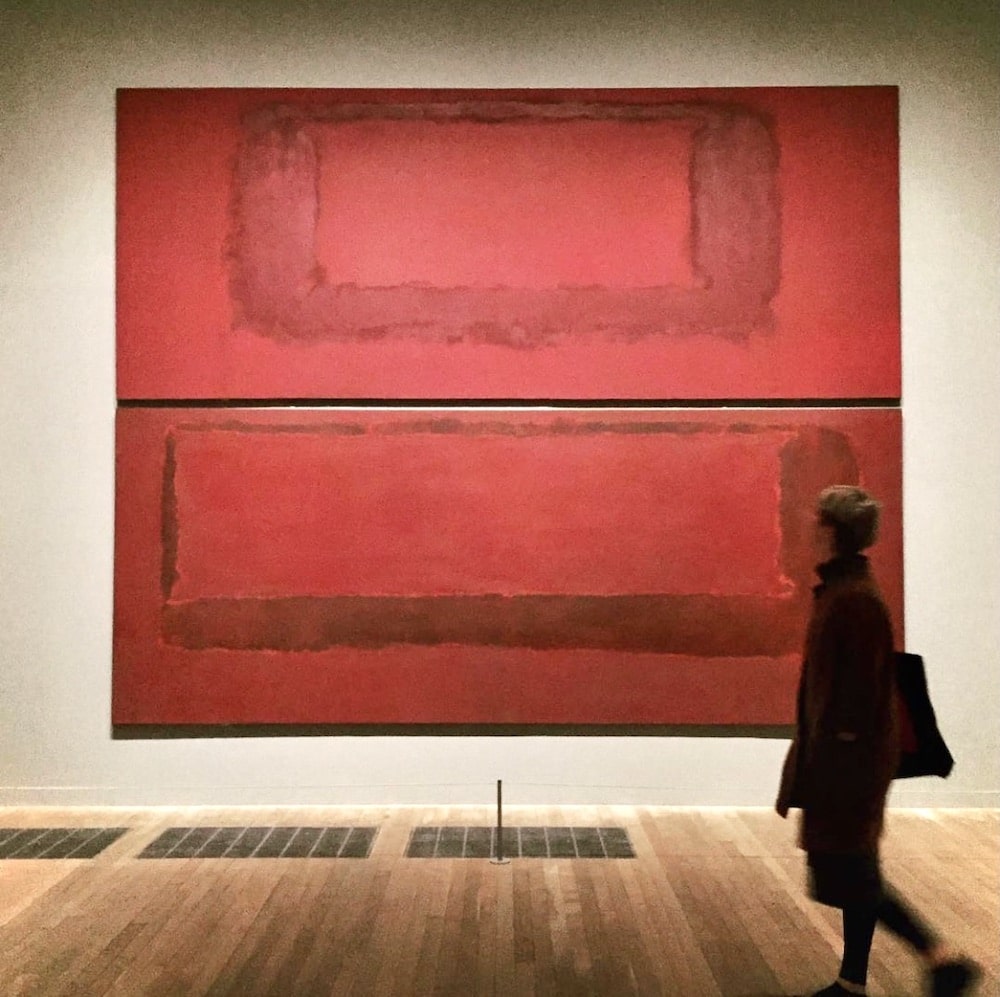

Thom was being a little ornery in this particular interview, and at one point he started waxing philosophical about the mythology that people lavish unto ‘Rock Stars’– e.g. the public’s inability to separate an artist’s personal life from their work— and he said that the beloved Rothko Room at the Tate Modern (below) was a perfect example.

Rothko was basically the Kanye West of his time, in the sense that he was super arrogant & always reminding people that his famous ‘color fields’ were so moving to people because he painting them with ecstatic raw emotion– the colors were supposed to capture feelings; of sadness, of joy, and in either case imbued with meaning.

Famously, people have been known to break down in front of Rothko’s paintings because they consider them so joyous.

Something I also didn’t know, however, was that Rothko later took his own life. And in relaying this anecdote, Thom Yorke deciphers a beautiful parable about life.

He said that when children go into the Rothko Room, they are overjoyed, because all they can see is the wonder and beautiful colors in the paintings.

Adults, however, go into the same room and all they can say is, in Thom’s parlance: “Wow, this is that poor sod who killed himself.” Only the adults who had hardened themselves to the world could see anything but joy in the paintings.

Because they knew Rothko’s back story, they imposed sadness onto what was in front of them– even if that wasn’t necessarily the intention of the work. People, moreover, do this all the time with musicians– and actors, and all litany of creative people.

I think about this story all the time– about how choosing to see beauty really is a choice— and I remembered it years later when I entered the Rothko Room for the first time and I instantly started to cry. It moved me.

I’m sure my visceral response to Rothko’s paintings had something to do with the fact that I was primed with this story. But entering the space felt like the culmination of some long, inward journey– towards happiness, wonder, and the incredible lightness of being. And herein lies a beautiful life lesson and parable.

‘One of the things that makes this extraordinary quality of Rothko’s canvases is that they are almost like blank cinema screens’

Rothko is a master of the sublime, but the lesson here really is more about life than art.

We filter reality through the lens of our experiences. If we hold deeply-held beliefs about ourselves, other people, or the state of the world, then we are guaranteed to have that experience. Whether it’s Thom Yorke’s enigmatic mythos, Rothko’s at times tragic life story, or the work of, say, a beloved illustrator or cartoonist– the real story comes from your personal reaction to the work.

Thus, negating the beauty in an artist’s work because of how their life ended is to shorten and disregard the meaning of that life. And if we do that to other people, how might this impact how we shorten and negate our own lives if and when unfortunate circumstance unfold? Because as we know, life will always deliver both ups and downs. Why let the downs control the narrative?

Ultimately, Thom Yorke’s perspective on Rothko is a lesson in the value of staying in the present moment. It’s about the beauty of decontextualization, and a reflection on what we often lose in the modern landscape of information overload.

When it comes to moving art, moreover, we often see with our hearts, not our minds. And in art as with life, over-articulation tends to ruin most things. (Like Allen Ginsberg once said: “First thought, best thought.”)

Getting in touch with our own visceral reactions to creative works is ultimately a truer and more fulfilling way to experience them. Again, this is a perfect metaphor for life, in that we don’t need to overthink it. When we overthink, we lose some of the magic.

So, take Thom Yorke’s hot take on Rothko more jaded viewers as the beautiful life lesson that it is. Relish the simple beauty of everything you encounter– and try not to let your head get in the way.

***

Related: 8 Amazing Paris Art Galleries to Add to Your Bucket List.

Leave a Reply